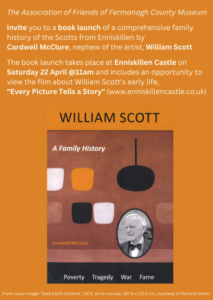

The Friends of Fermanagh County Museum is organising a book launch on Saturday, 22 April, at Enniskillen Castle, showcasing Cardwell’s “William Scott: A Family History” publication.

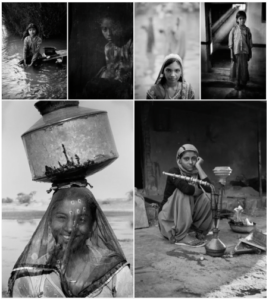

Every Picture Tells a Story (90 mins) feature film based on the early life of William Scott, directed by James Scott with Alex Norton, Phyllis Logan and Natasha Richardson will be shown as part of this event.

Enniskillen Castle Facebook Page

Enniskillen Castle Fermanagh County Museum Twitter

ABOUT THE BOOK:

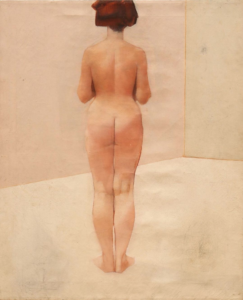

The author of this family history is Cardwell McClure, son of Mary McClure, née Scott, the younger sister of renowned artist William Scott CBE, RA. Cardwell remembers how his mother told him that William, when a teenager, would get his younger sister to sit for him lacking any other willing members of the family.

This book provides a first hand experience of the family’s trials through poverty, tragedy, war and fame.

There are twelve chapters in the book, eleven of which are devoted to each child, while the first chapter outlines the family beginnings in Glasgow, Scotland.

As Paul Teggart, the editor of the book says: “It is a wonderful story of triumph over adversity, sadness and happiness, and family loyalty. I can say, without a doubt, that the book is a labour of love and has only been completed after many years of dedicated research and a fine eye to detail by its author Cardwell McClure. It makes good reading whether you look at it from a family point of view or from an educational standpoint in examining the life and work of William Scott the artist.” A chronology of the Scott family dating from 1887 to 2022 is also being published alongside the Family History.

The Family History book can be bought on Amazon via the following link: www.amazon.co.uk

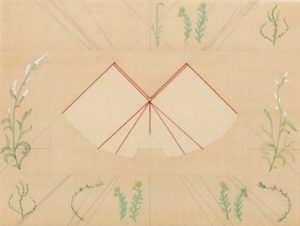

William Scott: A Family History which has taken many years in research, writing and editing partly due to the ill health of the author, Cardwell McClure, is lavishly illustrated with paintings by William Scott CBE RA.