By JOSEPH BERGER JAN. 1, 2017

It is perhaps the most significant artifact documenting the arrival of Jews in the New World: a small, tattered 16th-century manuscript written in an almost microscopic hand by Luis de Carvajal the Younger, the man whose life and pain it chronicled.

Until 1932, the 180-page booklet by de Carvajal, a secret Jew who was burned at the stake by the Inquisition in Spain’s colony of Mexico, resided in that country’s National Archives.

Then it vanished. The theft transformed the manuscript into an object of obsession, a kind of Maltese Falcon, for a coterie of Inquisition scholars and rare-book collectors. Almost nothing was heard about the document for more than 80 years — until it showed up 13 months ago at a London auction house. The manuscript was on sale for $1,500, because the house had little sense of its value.

But last year the relic caught the eye of a prominent collector of Judaica, Leonard Milberg, when it showed up for resale at the Swann Galleries in Manhattan. It was now priced at more than 50 times what it had sold for just a few months earlier in England. Mr. Milberg consulted a variety of experts, who told him it might be the actual manuscript, and worth as much as $500,000. They also warned him to be careful — the original had been reported stolen.

After a swirl of activity unleashed by Mr. Milberg’s inquiries, and financed by his generosity, the manuscript will be returning to the Mexican archives in March. For now, as part of the arrangement Mr. Milberg coordinated, the manuscript is on display through March 12 at the New-York Historical Society, part of an exhibition depicting the experience of the first Jews in North and South America.

“It is the earliest surviving personal narrative by a New World Jew,” said David Szewczyk, an expert in ancient books of the Americas, “and the earliest surviving worship manuscript and account of coming to the New World.”

The manuscript’s odyssey — from its creation in Mexico to its recent arrival in Manhattan — is a tale laced with intrigue.

De Carvajal was a Jew who posed as Catholic in New Spain, now Mexico, during a period when the Inquisition ruthlessly persecuted heretics and false converts with deportation, imprisonment, torture and grisly public executions.

De Carvajal, a trader, was arrested around 1590 as a proselytizing Jew and, while in prison, began writing a sometimes messianic memoir, the “Memorias,” on pages roughly 4 inches by 3 inches. In it, he called himself Joseph Lumbroso — Joseph the Enlightened. It begins: “Saved from terrible dangers by the Lord, I, Joseph Lumbroso of the Hebrew nation and of the pilgrims to the West Indies in appreciation of the mercies received from the hands of the Highest, address myself to all, who believe in the Holy of Holies and who hope for great mercies.”

The memoir tells how he learned from his father that he was Jewish, circumcised himself with an old pair of scissors, secretly embraced the faith and persuaded siblings to embrace it.

He was freed for a time — possibly so that the authorities could track his contacts with other secret Jews — and finished his autobiography, stitching it together with a set of prayers, the Ten Commandments and 13 principles of the Jewish philosopher Maimonides. Scholars believe he made it miniature so he could conceal it inside a coat or pocket. In 1596, after having been found guilty again of observing Jewish practices, he was burned at the stake. He was 30.

His manuscript, discovered in his clothing, eventually ended up in the National Archives, which by the 1930s was located in a building adjacent to the presidential palace.

How the book disappeared remains a matter of conjecture. At the time, at least three scholars were delving into the atlas-size volumes of the Inquisition’s proceedings against de Carvajal. They have all been suspects of one kind or another over the years. One of them, a historian on the archives staff who was writing a book on the de Carvajal family, accused a rival of the theft. The rival, Jacob Nachbin, a Yiddish-speaking Polish and Jewish history professor who had taught at Northwestern University in Illinois and what is now New Mexico State University in Las Cruces, spent roughly three months in jail but was released for insufficient evidence. Some scholars think his accuser may have actually been guilty.

The whereabouts of the manuscript remained a mystery until its emergence in London. One scholar, Rabbi Martin A. Cohen of Hebrew Union College in New York, said in an interview that he believes he read the manuscript at the Mexican archives in the 1950s while doing research for “The Martyr,” a 1973 book on de Carvajal. Other scholars think it more likely that what he saw was a transcription.

In London in December 2015, Bloomsbury Auctions listed the de Carvajal materials in its catalog as “three small devotional manuscripts.” The catalog did not mention de Carvajal. It described the manuscript as a 17th-or 18th-century work and said it had come “from the library of a Michigan family, and in their possession for several decades.” Timothy Bolton, Bloomsbury’s Western manuscripts chief, said he could not identify the family because “one of the fundamental cornerstones of the auction world is our client’s privacy.”

The subsequent Bloomsbury buyer, described by a Swann official only as a rare-book dealer, brought the manuscript to Swann, which priced it at $50,000 to $75,000. Though some experts value it closer to $500,000, Swann thought the de Carvajal manuscript to be a transcript — a very old copy — not the original in de Carvajal’s hand, and listed it as such in its catalog.

That’s where it was spotted last summer by Mr. Milberg, 85, the Flatbush, Brooklyn-reared owner of a Manhattan commercial finance company who collects Judaica and Irish poetry. He decided to buy the manuscript “copy” and include it in the planned exhibition at the New-York Historical Society, which was to include many pieces from his Judaica collection. Then he was going to donate it to Princeton University, his alma mater.

But experts he consulted, like Ilan Stavans, a professor of Latin American culture at Amherst College, convinced him that it was both authentic and stolen. (One reason Mr. Milberg believes it to be the original: No transcriber, he said, would have bothered to make the handwriting so tiny.)

Swann ultimately pulled the manuscript from the sale, and Mexican curators confirmed its authenticity.

Rick Stattler, head of Swann’s rare-book department, said that when he realized he had de Carvajal’s original, “I actually had the hairs go up on my arm.”

Mr. Milberg told Diego Gómez Pickering, Mexico’s consul-general in New York, that he would try to arrange a return of the manuscript. But he needed a few months so that it could be displayed in New York. Mr. Gómez Pickering agreed.

To avoid any argument over rightful possession, Mr. Milberg agreed to pay Swann’s consignor $10,000 — still a tidy profit. Swann got $2,500 for its trouble from Mr. Milberg. And a dealer who helped him coordinate the transactions, William Reese, received $25,000 for his labors.

Mr. Milberg also insisted that digital copies be made for Princeton and the Spanish-Portuguese Synagogue in Manhattan. He said that highlighting such objects is his way of “getting back at anti-Semitism.”

“I wanted to show that Jews were part of the fabric of life in the New World,” he said. “This book was written before the Pilgrims arrived.”

VIA The New York Times and the BAHS blog.

Barlow (b. 1990, Jackson, Mississippi) studied at the New York Studio School with Carole Robb and at the University of Southern Mississippi before receiving his MFA from the Slade School of Fine Art, London. The artist now lives and works in London. Barlow’s large-scale expressive works on linen are evocative explorations of spatial relationships, communication, color, shape and scale. On the recent works included in this exhibition, Barlow writes:

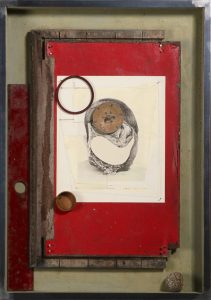

Barlow (b. 1990, Jackson, Mississippi) studied at the New York Studio School with Carole Robb and at the University of Southern Mississippi before receiving his MFA from the Slade School of Fine Art, London. The artist now lives and works in London. Barlow’s large-scale expressive works on linen are evocative explorations of spatial relationships, communication, color, shape and scale. On the recent works included in this exhibition, Barlow writes: Film & Photography and a Master of Arts Degree from New York University. He studied with Robert Mapplethorpe, Duane Michals and Arnold Newman. Neleman’s collaged works, in the tradition of Joseph Cornell, are put forth in distressed iron frames housing astute composites of old and new, found and created objects addressing sexuality, mortality and identity. On the assemblages, Neleman states:

Film & Photography and a Master of Arts Degree from New York University. He studied with Robert Mapplethorpe, Duane Michals and Arnold Newman. Neleman’s collaged works, in the tradition of Joseph Cornell, are put forth in distressed iron frames housing astute composites of old and new, found and created objects addressing sexuality, mortality and identity. On the assemblages, Neleman states:

Many notable artists — among them Dan Flavin, Sol LeWitt, and Brice Marden — worked at museums early in their careers, usually as security guards, but few kept one foot in the studio and one in a museum for three decades. George Negroponte managed to do just that.

Many notable artists — among them Dan Flavin, Sol LeWitt, and Brice Marden — worked at museums early in their careers, usually as security guards, but few kept one foot in the studio and one in a museum for three decades. George Negroponte managed to do just that.