Virva Hinnemo appears to enjoy blurring lines that have always defined classic formalism as well as the borders between pure abstraction and naturalism.

Although the cardboard she adopted as a primary medium a few years ago is still present in the Anita Rogers Gallery in SoHo, Virva Hinnemo’s focus has lately shifted back to paper and, ultimately, to canvas.

In the solo show “Four Feet,” the Springs artist moves back and forth freely between mediums and different forms of supports, including a rather complicated piece, “Under the House,” which is painted on framed plywood and propped up with wooden blocks, resembling sculpture on an improvised and unusual pedestal.

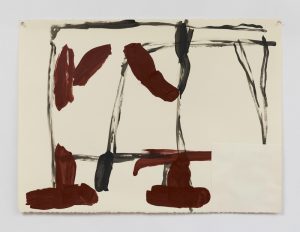

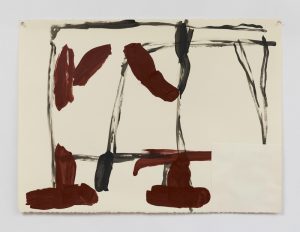

The artist appears to enjoy blurring lines that have always defined classic formalism as well as the borders between pure abstraction and naturalism. How else to explain works with titles such as “Waterfront,” “Still Life,” and “Laundry” that also evoke those subjects in the subtlest ways?

Recycling and repurposing are appealing trends in art-making and they don’t appear to be losing steam. As humans create more and more detritus, artists have seized the day and the trash, to transform it into something more pleasantly enduring. These pieces can deliver both depth, with their inherent cultural critique, and a sense of aesthetic surprise and delight (“See what they did with that tire, radio, computer monitor, etc.?”).

Ms. Hinnemo’s cardboard pieces include a bit of play, as well. The wide daubs that make up her painting “Still Life” actually come from a bright blue-and-white striped box top. It can be debated whether those are Cezanne apples in a bowl or Morandi vases, but what is indisputable is that the piece has an air of lighthearted fun.

“Two Plus Two” looks like a face. The artist’s cutouts — both those she made herself, as in “Close to the Wall,” and prefabricated, as in “Horizon” — address the sculptural properties of the support, introducing an air of uncertainty about how ultimately to define these objects.

Nowhere is that uncertainty more apparent than in “Under the House,” in which her acrylic paint seems to evoke flames in a stove or furnace, with the black, gray, and white palette looking like coal and ash. The title could be reassuring (hearth and home) or ominous (what lies beneath? unchecked passions or peril?). A simple panel is not a radical support for a painting, but what of the framing? It could be a shed or cellar door or some other found bit of hardware. The rough blocks that keep it upright don’t appear to be part of the piece; their measurements are not included in the work’s description. Yet, purely functional or not, it is hard to divorce their presence from the overall impression of the piece.

In “Laundry,” a work on paper, she places paper over a painted section in the tradition of collage, but the beige paper matches the background in the way correction tape covers up mistakes in text. That there is still a hint of the painting concealed beneath it gives the piece a mysterious air. What was the motivation to hide what is underneath?

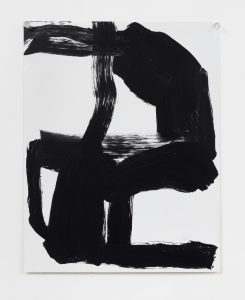

Those pieces leave a lot to contemplate, but the canvas paintings are the real treat in the show. They, too, benefit from extended viewing. A quick pass might offer hints of Robert Motherwell, Franz Kline, even Mark Tobey, but it wouldn’t reveal the depth of the artist’s unique approach. Seemingly just black and white with shadings of gray, almost all of them have some color in their underpainting. In “Ground Glow,” it is a purplish red, maybe wine, maybe something more sanguine. In the piece that shares the title of the show, “Four Feet,” it is a lovely, peaceful blue thinned with white.

In some canvases, central portions are left blank, creating voids and pauses in the composition. “The Crossing,” a rare vertical piece in the show, seems to suggest all manner of meanings, from the soaring spires of the architectural crossing of a medieval church to the harrowing journey war refugees are still undertaking to leave their ravaged countries. Or, to take it down a notch, it could be the energy of a busy city intersection. That so much allusion could be packed into these paintings speaks to their emotive qualities and to their restraint.

The exhibition will remain on view through April 21.

by Jennifer Landes

The exhibition will showcase drawings by Gloria Ortiz-Hernández, a Colombian artist whose work is included in the permanent collections of museums such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York and in private collections throughout the United States and in Switzerland, Brazil and Colombia. Robert Szot, an artist from Texas currently based in Brooklyn, will show collages and paintings. Jan Cunningham, an American artist, will show her “Arabesque Paintings” of 2016 and 2017, celebrating the materiality of color and light and juxtaposing the anticipated with the unexpected.

The exhibition will showcase drawings by Gloria Ortiz-Hernández, a Colombian artist whose work is included in the permanent collections of museums such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York and in private collections throughout the United States and in Switzerland, Brazil and Colombia. Robert Szot, an artist from Texas currently based in Brooklyn, will show collages and paintings. Jan Cunningham, an American artist, will show her “Arabesque Paintings” of 2016 and 2017, celebrating the materiality of color and light and juxtaposing the anticipated with the unexpected.

One of the artist’s most significant works on display is a large-scale six-part canvas painting of Knossos, the largest Bronze age archaeological site in located on the Greek Island of Crete. In this painting, Rogers pulls the ancient ruins from the past into the present by using abstract designs such as the periwinkle-blue floral patterns that frame the image and bold colors including the bright and dark shades of green on the surrounding grass.

One of the artist’s most significant works on display is a large-scale six-part canvas painting of Knossos, the largest Bronze age archaeological site in located on the Greek Island of Crete. In this painting, Rogers pulls the ancient ruins from the past into the present by using abstract designs such as the periwinkle-blue floral patterns that frame the image and bold colors including the bright and dark shades of green on the surrounding grass. Visit the gallery’s website.

Visit the gallery’s website.